The table of contents for the rest of this paper, A Layman’s Guide to Anthropogenic Global Warming (AGW) is here. Free pdf of this Climate Skepticism paper is here and print version is sold at cost here.

Kyoto Treaty

In the mid-1990’s, a number of western nations crafted a CO2-reduction treated named Kyoto for the city in which the key conference was held. The treaty called for signatory nations to roll back their CO2 emissions to below 1990 levels by a target date of 2012. Japan, Russia, and many European nations signed the treaty; the United States did not. In fact, the pact was ratified by 141 nations, but only calls for CO2 limits in 35 of these (so the other 106 were really going out on a limb signing it). China, India, Brazil and most of the third world are exempt from its limits.

We will discuss the costs and benefits of CO2 reduction a bit later. However, it is instructive to look at why Kyoto was crafted the way it was, and why the United States refused to sign, even when Al Gore was vice-president.

The most obvious flaw is that the entire developing world, including China, SE Asia, and India, are exempt. These countries account for 80% of the world’s population and the great majority of growth in CO2 emissions over the next few decades, and they are not even included. If you doubt this at all, just look at what the economic recovery in China over the past months has done to oil prices. China’s growth in hydrocarbon consumption will skyrocket over the coming years, and China is predicted to have higher CO2 production than the United States by 2009.

The second major flaw with the treaty is that European nations cleverly crafted the treaty so that the targets were relatively easy for them to make, and very difficult for the United States to meet. Rather than freezing emissions at current levels at the time of the treaty, or limiting carbon emission growth rates, the treaty called for emissions to be rolled back to below 1990 levels. Why 1990? Well, a couple of important things have happened since 1990, including:

a. European (and Japanese) economic growth has stagnated since 1990, while the US economy has grown like crazy. By setting the target date back to 1990, rather than just starting from day the treaty was signed, the treaty effectively called for a roll-back of economic growth in the US that other major world economies did not enjoy.

b. In 1990, Germany was reunified, and Germany inherited a whole country full of polluting inefficient factories from the old Soviet days. Most of the dirty and inefficient Soviet-era factories have been closed since 1990, giving Germany an instant one-time leg up in meeting the treaty targets, but only if the date was set back to 1990, rather than starting at the time of treaty signing.

c. Since 1990, the British have had a similar effect from the closing of a number of old dirty Midlands coal mines and switching fuels from very dirty coal burned inefficiently to more modern gas and oil furnaces and nuclear power.

d. Since 1990, the Russians have an even greater such effect, given low economic growth and the closure of thousands of atrociously inefficient communist-era industries.

It is flabbergasting that US representatives could allow the US to get so thoroughly out-manuevered in these negotiations. Does anyone in the US really want to roll back the economic gains of the nineties, while giving the rest of the world a free pass? Anyway, as a result of these flaws, and again having little to do with the global warming argument itself, the Senate voted 95-0 in 1997 not to sign or ratify the treaty unless these flaws (which still exist in the treaty) were fixed. Then-Vice-President Al Gore agreed that the treaty should not be signed without modifications, which were never made and which Europeans were never going to make.

By the way, enough time has elapsed that we have data on the progress of various countries in meeting these targets. And if you leave out various accounting games with offsets of dubious value, most all the European nations, despite all the advantages described above, are still missing their targets. The political will simply does not exist to hamstring their economies to the extent necessary to roll back CO2 growth. Actual growth rates for CO2 emissions have been (source UN):

|

United States |

Europea Union |

|

|

1990-1995 |

6.4% |

-2.2% |

|

1996-2000 |

10.1% |

2.2% |

|

2001-2004 |

2.1% |

4.5% |

You can see that the Europeans positioned themselves well in the 1990’s to make their targets. Realize that as the treaty was negotiated, they already had a good idea of these numbers for 1990-1995 and even a few years beyond. They knew that by selecting a 1990 baseline, they were already on target to meet the goals and the US would be far behind. Again, realize that the 1990-2000 EU performance on CO2 production had nothing to do with post-Kyoto regulatory responses and everything to do with the economic fundamentals we outlined above that would have existed with or without the treaty.

Since 2000, however, it has been a different story. European emissions have increased as their economies have recovered, at the same time the US experienced a post-9/11 slowdown.

By the way, the US is generally the great Satan in AGW circles because its per capita CO2 production is the highest in the world. But this is in part because our economic output per capita is close to the highest in the world. The US is about in the middle of the pack in efficiency, though behind many European countries which have much higher fuel taxes and heavier nuclear investments.

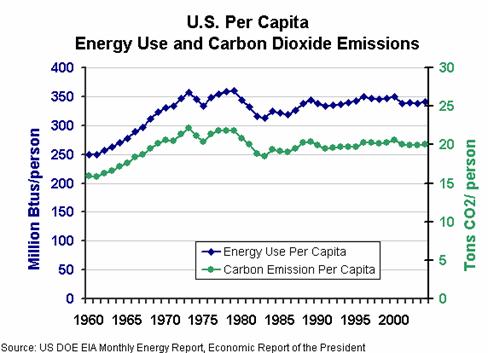

As an interesting side note, the US per capita CO2 emissions, as show below, have actually been flat to down since the early 1970’s. To the extent that Europe is doing better at CO2 reduction than the US, it may actually be more of an artifact of their declining populations vs. America’s continued growth.

Finally, if you get really tired of the US-bashing, you can take some comfort that though the US is the #1 per capita producer of CO2, of which we are uncertain is even harmful, we have done a fabulous job reducing many other pollutants we are much more certain are harmful. For example, the US has much lower SO2 production than most European nations and the water quality is better. One could argue that the US has spent its abatement dollars on things that really matter.

Cost of the Solutions vs. the Benefits: Why Warmer but Richer may be Better than Colder and Poorer

If you get beyond the hard core of near religious believers in the massive warming scenarios, the average global warming supporter would answer this paper by saying: "Yes there is a lot of uncertainty, but though the doomsday warming scenarios via runaway positive feedback in the climate can’t be proven, they are so bad that we need to cut back on CO2 production just to be on the safe side."

This would be a perfectly reasonable approach if cutting back on CO2 production was nearly cost-free. But it is not. The burning of hydrocarbons that create CO2 is an entrenched part of our lives and our economies. Forty years ago we might have had an easier time of it, as we were on a path to dramatically cut back on CO2 production via what is still the only viable technology to massively replace fossil fuel consumption — nuclear power. Ironically, it was environmentalists that shut down this effort, and power industries around the world replaced capacity that would have gone nuclear mostly with coal, the worst fossil fuel in terms of CO2 production (per BTU of power, Nuclear and hydrogen produce no CO2, natural gas produces some, gasoline produces more, and coal produces the most).

Just halting CO2 production at current levels (not even rolling it back) would knock several points off of world economic growth. Every point of economic growth you knock off guarantees you that you will get more poverty, more disease, more early death. If you could, politically, even make such a freeze stick, you would lock China and India, nearly 2 billion people, into continued poverty just when they were about to escape it. You would in the process make the world less secure, because growing wealth is always the best way to maintain peace. Right now, China can become wealthier from peaceful internal growth than it can from trying to loot its neighbors. But in a zero sum world created by a CO2 freeze, countries like China would have much more incentive to create trouble outside its borders. This tradeoff is often referred to as a cooler but poorer world vs. a richer but warmer world. Its not at all clear which is better.

What impact, warming?

We’ve already discussed just how much the popular media has overblown the effect of warming. Sea levels may rise, but only by 15 inches in one hundred years, and even that based on arguably over-inflated IPCC models. There is no evidence that weather patterns will be more severe, or that diseases will spread, or that species will be threatened by warming. And, since most of the warming has been and will be concentrated in winter and nights, we will see rising temperatures more in a narrowing of temperature variability rather than a drastic increase in summer high temperatures. Growing seasons, in turn, will be longer and deaths from cold, which tend to outnumber heat-related deaths, will decline.

What impact, Intervention?

While the Kyoto treaty was a massively-flawed document, with current technologies a Kyoto type cap and trade approach is about the only way we have available to slow or halt CO2 emissions. And, unlike the impact of warming on the world, the impact of such a intervention is very well understood by the world’s economists and seldom in fact disputed by global warming advocates. Capping world CO2 production would by definition cap world economic growth at the rate of energy efficiency growth, a number at least two points below projected real economic growth. In addition, investment would shift from microprocessors and consumer products and new drug research and even other types of pollution control to energy. The effects of two points or more lower economic growth over 50-100 years can be devastating:

- Remember the power of compounded growth rates we discussed earlier. A world real economic growth rate of 4% yields income fifty times higher in a hundred years. A world real economic growth rate two points lower yields income only 7 times higher in 100 years. So a two point reduction in growth rates reduces incomes in 100 years by a factor of seven! This is enormous. It means, literally, that on average everyone in a cooler world would make 1/7 what they would make in a warmer world.

- Currently, there are perhaps a billion people, mostly in Asia, poised to exit millennia of subsistence poverty and reach the middle class. Global warming intervention will likely consign these folks to continued poverty. Does anyone remember that old ethics problem, the one about having a button that every time you pushed it, you got a thousand dollars but someone in China died. Global warming intervention strikes me as a similar issue – intellectuals in the west feel better about man being in harmony with the Earth but a billion Asians get locked into poverty.

- Lower world economic growth will in turn considerably shorten the lives of billions of the world’s poor

- A poorer world is more vulnerable to natural disasters. While AGW advocates worry (needlessly) about hurricanes and tornados in a warmer world, what we can be certain of is that these storms will be more devastating and kill more people in a poorer world than a richer one.

- The unprecedented progress the world is experiencing in slowing birth rates, due entirely to rising wealth, will likely be reversed. A cooler world will not only be poorer, but likely more populous as well. It will also be a hungrier world, particularly if a cooler world does indeed result in lower food production than a warmer world

- A transformation to a prosperous middle class in Asia will make the world a much safer and more stable place, particularly vs. a cooler world with a billion Asian poor people who know that their march to progress was halted by western meddling.

- A cooler world would ironically likely be an environmentally messier world. While anti-growth folks blame all environmental messes on progress, the fact is that environmental impact is a sort of inverted parabola when plotted against growth. Early industrial growth tends to pollute things up, but further growth and wealth provides the resources and technology to clean things up. The US was a cleaner place in 1970 than in 1900, and a cleaner place today than in 1970. Stopping or drastically slowing worldwide growth would lock much of the developing world, countries like Brazil and China and Indonesia, into the top end of the parabola. Is Brazil, for example, more likely to burn up its rain forest if it is poor or rich?

The Commons Blog links to this study by Indur Goklany on just this topic:

If global warming is real and its effects will one day be as devastating as some believe is likely, then greater economic growth would, by increasing greenhouse gas (GHG) emissions, sooner or later lead to greater damages from climate change. On the other hand, by increasing wealth, technological development and human capital, economic growth would broadly increase human well-being, and society’s capacity to reduce climate change damages via adaptation or mitigation. Hence, the conundrum: at what point in the future would the benefits of a richer and more technologically advanced world be canceled out by the costs of a warmer world?

Indur Goklany attempted to shed light on this conundrum in a recent paper presented at the 25th Annual North American Conference of the US Association for Energy Economics, in Denver (Sept. 21, 2005). His paper — "Is a richer-but-warmer world better than poorer-but-cooler worlds?” — which can be found here, draws upon the results of a series of UK Government-sponsored studies which employed the IPCC’s emissions scenarios to project future climate change between 1990 and 2100 and its global impacts on various climate-sensitive determinants of human and environmental well-being (such as malaria, hunger, water shortage, coastal flooding, and habitat loss). The results indicate that notwithstanding climate change, through much of this century, human well-being is likely to be highest in the richest-but-warmest world and lower in poorer-but-cooler worlds. With respect to environmental well-being, matters may be best under the former world for some critical environmental indicators through 2085-2100, but not necessarily for others.

This conclusion casts doubt on a key premise implicit in all calls to take actions now that would go beyond “no-regret” policies in order to reduce GHG emissions in the near term, namely, a richer-but-warmer world will, before too long, necessarily be worse for the globe than a poorer-but-cooler world. But the above analysis suggests this is unlikely to happen, at least until after the 2085-2100 period.

Policy Alternatives

Above, we looked at the effect of a cap and trade scheme, which would have about the same effect as some type of carbon tax. This is the best possible approach, if an interventionist approach is taken. Any other is worse.

The primary other alternative bandied about by scientists is some type of alternative energy Manhattan project. This can only be a disaster. Many scientists are technocratic fascists at heart, and are convinced that if only they could run the economy or some part of it, instead of relying on this messy bottom-up spontaneous order we call the marketplace, things, well, would be better. The problem is that scientists, no matter how smart they are, miss with their bets because the economy, and thus the lowest cost approach to less CO2 production, is too complicated for anyone to understand or manage. And even if the scientists stumbled on the right approaches, the political process would just screw the solution up. Probably the number one alternative energy program in the US is ethanol subsidies, which are scientifically insane since ethanol actually increases rather than reduces fossil fuel consumption. Political subsidies almost always lead to investments tailored just to capture the subsidy, that do little to solve the underlying problem. In Arizona, we have thousands of cars with subsidized conversions to engines that burn multiple fuels but never burn anything but gasoline. In California, there are hundreds of massive windmills that never turn, having already served their purpose to capture a subsidy. In California, the state bent over backwards to encourage electric cars, but in fact a different technology, the hybrid, has taken off.

Besides, when has this government led technology revolution approach ever worked? I would say twice – once for the Atomic bomb and the second time to get to the moon. And what did either get us? The first got us something I am not sure we even should want, with very little carryover into the civilian world. The second got us a big scientific dead end, and probably set back our space efforts by getting us to the moon 30 years or so before we were really ready to do something about it or follow up the efforts.

If we must intervene to limit CO2, we should jack up the price of fossil fuels with taxes, or institute a cap and trade scheme which will result in about the same price increase, and the market through millions of individual efforts will find the lowest cost net way to reach whatever energy consumption level you want with the least possible cost. (The only real current alternative that is rapidly deploy-able to reduce CO2 emissions anyway is nuclear power, which could be a solution but was killed by…the very people now wailing about global warming.)

The table of contents for the rest of this paper, A Layman’s Guide to Anthropogenic Global Warming (AGW) is here. Free pdf of this Climate Skepticism paper is here and print version is sold at cost here.